Since I don’t have any current topics, it’s probably a good time to continue showing you chapters from my unfinished adventure book. In its current form, this chapter follows directly after the introduction. I’ve fleshed it out a little for this post, but the next one is not yet written, so who knows what will be the next step on these pages.

Methods

When it comes to playing adventure games, it is clear from the beginning that there will be puzzles to overcome, so a number of methods to solving them suggest themselves. These methods range from stumbling through the game world until something unexpected happens, to meticulously writing down every piece of information and combining everything logically, to treating the game like a pure challenge and trying everything to crack it. Which of them are suitable differs from game to game, and mostly we don’t need a very forceful approach to be successful.

That said, there are times when playing nice won’t do, and so we will study all sorts of methods throughout this book, from the meek to the bold, and from the careful to the aggressive.

Conventions

There are certain ways to represent the world that have become standards in the world of adventure gaming. It seems obvious now that the player character should have an inventory of things they are carrying, that they should be able to move between locations, and that certain other events take place while they are exploring their surroundings – but those things needed to be established at some point to make up the adventure game genre.

All the mentioned considerations came up in the very first adventure game (simply called Adventure, later often named Colossal Cave after the real-world location it takes place in, and nowadays sometimes affectionately referred to as ADVENT for the file naming conventions of yore), and there were also some others that went out of fashion after a while. We will examine those conventions in this section, so that you get an idea of what might await you.

Firstly, you must know about the interface. As mentioned in the introduction, we will focus on the text adventure genre, so aside from the text to read you also have to enter text. Your input should generally have the form of short commands, and you will need to figure out how complex those commands can be, either by reading the instructions or by experimenting – mostly the latter, though, since no instruction sheet or manual can explain every detail of the game. The next section has some more advice about the ways you can communicate with the game, and section xx details how to find out more about its commands.

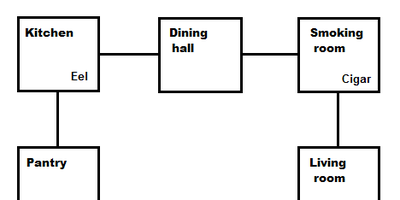

One of the most interesting and practical conventions is the compass: almost all text adventures can be navigated by using compass directions such as “north”, “west” or “southeast” (typically not “south-southwest”, though). The game will assume that you have a perfect sense of orientation in that you always know which way you are facing, even underground or underwater. There are exceptions, of course, like navigating by giving the name of the location you want to enter, or relative directions such as on a ship.

You always have an inventory (usually examined with the command “inventory”), but there are no guarantees as to how many things you can carry. In modern games, there is usually no real limit, but it used to be normal to be able to carry no more than two or three items. Some games consider the size or weight of the objects you carry, but most just impose some arbitratry limit.

Finally, among the things that happen while time passes, there are problems such as hunger, thirst and the need to sleep.

Another important convention is that in adventure terms, every location is called a room, whether it is a room in a house, an open field or a path in the woods. References to moving between rooms in later sections might mean any of these, and in the context of gameplay there is little difference in meaning.